The 64-square madhouse, a short story by Fritz Leiber published in 1962 in IF worlds of science fiction. It tells of the first super chess tournament in which a computer is participating. It is freely available on the Project Gutenberg site. In today’s post, I will be giving you my impressions as I read the whole thing. As a bonus, there is a picture, which I will discuss in due course.

We are introduced to Sandra, some kind of journalist trying but failing to find human interest stories in the margins of the big tournament. She is not at all happy about the fact that there are, and I quote, Siamese-twin clocks. Lucky for her, those old-style double clocks are disappearing fast. Leiber does not appear to have predicted that.

She meets a genial older man who coaxes her away from the playing hall with the promise of a drink. He tells her that the computer is able to look eight moves ahead — that is, eight ply — and decides its move based on its evaluations of the resulting positions. Eight ply! And this thing is supposed to compete with the world elite? There’s toilet paper with more plies! It must have a seriously impressive evaluation function.

We find out that the old man she’s conversing with is called Savilly and that one of his colleagues, one who has played fifty simultaneous games blindfolded, is called Igor Jandorf. I smell shenanigans here on the author’s part. Savilly is probably a thinly veiled cartoon of Tartakower while Jandorf is Najdorf.

Oh yes, there are shenanings! The list of players includes Mikhail Votbinnik, Vassily Lysmov, and even the up-and-coming William Angler.In the first round, the machine plays against Hungarian Grabo. Shortly after, we learn that a certain Simon Great, a psychologist, has been working on the machine. A fine pun.1

We learn that the time control is 30 moves in 2 hours followed by 15 moves every hour. Clearly, there are some things our author did not foresee. The machine’s game against Grabo is underway. The human has a strong attacking position, but he is getting very nervous. He blunders a mate in three! The machine has scored its first point.

The beginning of the tournament being over, the story speeds up. In a few paragraphs, we learn that the machine’s second-round game against Sherevsky is adjourned in a balanced endgame and that, in the third round, Lysmov managed to outsmart the programmers using a clever trap. He allowed a combination which seemed to win a piece in ten moves, but instead ran into checkmate in twelve.2 The horizon effect strikes! Then the machine strikes back with four victories; Great has added an opening book. The adjourned game with Sherevsky ends in a draw.

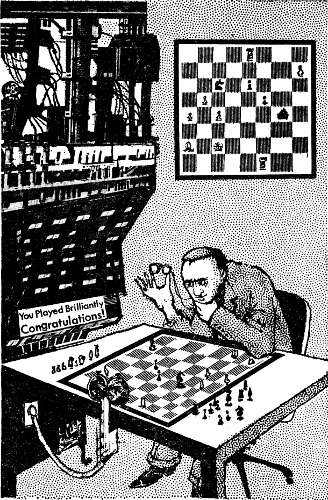

Then something interesting happens. The machine has to play against Krakatower and gets a dominating position, but then it breaks down. It takes fifty minutes to repair it and by then, the machine had to make fifteen moves in ten minutes. This is where we see the illustration at the top of this page. If you haven’t looked at it closely, I would invite you to do so now. Look at the black square on Krakatower’s right. Consider the vast differences between the position on the board and the demonstration board behind it. Ponder the ridiculous placement of the deformed twin clocks, way outside of the player’s reach. Meditate over the failings that led you to see this monstrosity. Also, there’s no score sheet. Bah.

In the last round, the machine, which is leading by now, has to play against Angler. Now Angler is a barely camouflaged version of Bobby Fischer who, when this story appeared, was the big hope of American chess.3 So, naturally, he’s going to beat the machine. But how?

In a pretty clever way, it turns out. He guesses correctly that the machine opening book comes from Modern Chess Openings and he has pored over it and found a big mistake. Using that, he beats the machine easily and takes tournament victory.

Final verdict: It’s not bad at all. It is not the most exciting plot ever and that Angler wins in the end is rather predictable. But the writing is quite good. And the author clearly did some research about what a chess computer could look like and how it could work. But he understandably didn’t predict the rapid progress in computing.

1. [Personally, I like my puns projective.] ↩

2. [It turns out the machine is actually running at 10 ply.] ↩

3. [There’s also the anglerfish, which gives a new connection to Fischer..] ↩