Suppose, just for the sake of argument, that you end up in Hannover. Assume, still completely hypothetically, that you have strolled through the Herrenhäuser Gärten and around the Maschsee, that you have noticed that the curved lift in the Neues Rathaus is not in operation, and that the famous Roten Faden is not as trustworthy as its mythological counterpart that guided Theseus out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth. What do you do? Well, you go to the Landesmuseum1 to see a pretty standard collection of stuffed animals and fossils and a rather extensive gallery with a few pretty nice paintings, some horrible ones, and a whole load of middle-of-the-road ones. One of the last category is our subject today: Eduard Haaga’s Schachstilleben.

Who is Eduard Haaga, you ask? Well, fuck if I know. Some dude, I guess, who painted. The Landesmuseum has a card next to this painting saying he was from Munich and claiming it was made in 1889. An internet search will turn up a few more paintings but very little else. So if you want history or art criticism, I’m afraid you will have to find a different blog. The only thing I can tell you is whether his chess skills are up to scratch.

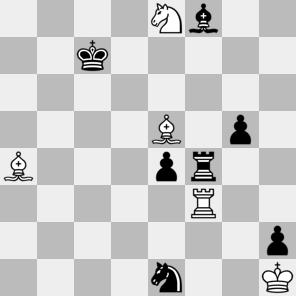

So let us find out! The pieces are non-standard; since this still-life was painted in the 19th century, this is to be expected. But whoever was playing didn’t put his pieces neatly in the middle of their squares like a civilised gentleman. This makes identifying the position considerably harder, as does the fact that the board is set up wrongly once more. Here is the result of my work, it’s not perfect, but I did my best:2

If my reconstruction is correct – and that’s a big if – then this is the first time, I think, that I can determine the last move: it must have been Nd6-e8+. I can also determine the next move: if it is not Kd8, the white rook will give a check, and the rook on f4 will fall, giving white excellent winning chances. If black does play Kd8, then the result is an unbelievable mess where either side could be better and the verdict might change with every move. White is a piece up, but black has three pawns for it, some of which are already very far advanced.

If my reconstruction is correct – and that’s a big if – then this is the first time, I think, that I can determine the last move: it must have been Nd6-e8+. I can also determine the next move: if it is not Kd8, the white rook will give a check, and the rook on f4 will fall, giving white excellent winning chances. If black does play Kd8, then the result is an unbelievable mess where either side could be better and the verdict might change with every move. White is a piece up, but black has three pawns for it, some of which are already very far advanced.

At this point, I usually draw my conclusions, but I can’t do that here; I would have to paint them. As my artistic qualities are unfavourably comparable to those of an average cassava root, I will spare you them.3

Realism: 2/5 With so few pieces, it is hard to make a really improbable position, but mister Haaga managed to do it. What on earth brought the white rook to f3, where it is attacked thrice? What could black have possibly played before Ne8+?

Probable winner: White seems to have the best chances; even after Kd8, Stockfish on high depth gives an advantage of almost a pawn to white. Converting that advantage is another problem, however.

1. [And you plagiarise your own blog posts.]↩

2. [To do your own paintings.]↩

3. [If you are masochistic enough to really want a taste, I can refer you to a previous blog post and the stunning image on display there.]↩